“I would have to question whether or not she (Janet Protasiewicz) looked at us as humans or she looked at us as the ‘N-word.’” -Denise Goggans, the twins’ aunt

TOP FACTS

- A black grandmother, Margaret Hudson, lost custody of her grandchildren after it was determined her home was too small. “I was raised in a family, and we stick together. That’s what families do,” said Hudson, who fought the case to the Supreme Court.

- Janet Protasiewicz, acting as an assistant district attorney, was the prosecutor who fought tooth-and-nail to take the 5-year-old twins from the black grandmother and give them to a single, childless white woman on Milwaukee’s south side.

- A black Milwaukee judge, Joe Donald, ruled the twins should stay with the grandmother, saying she “never wavered in her desire or her love for her grandchildren.” But Protasiewicz appealed the judge’s decision all the way to the Wisconsin Supreme Court even after the grandmother purchased a 6-bedroom home.

- The twins would eventually be placed with the adoptive single white mother favored by Protasiewicz who lived in an even smaller two-bedroom home on Milwaukee’s far south side. But the twins ended up having a difficult life in some ways and, by age 13, they were returned to their birth family after years of traumatic separation.

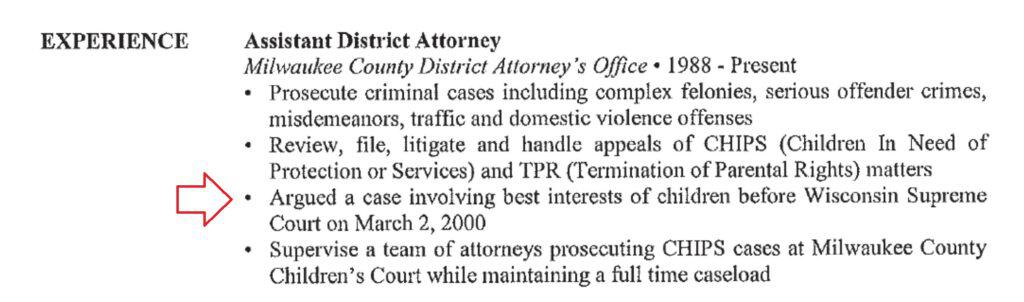

- Protasiewicz wrote that she had the “honor” of arguing the case before the state Supreme Court and said the state “prevailed.” She described working on the case as a “very fulfilling experience” and “rewarding.” We asked Protasiewicz today if she regrets the decision. She did not respond.

- This happened during the time frame when Protasiewicz allegedly used racial slurs to refer to black parents in Children’s Court and other cases.

Around the same time she is accused of using a vile racial slur to refer to black parents in Children’s Court, Janet Protasiewicz, then a prosecutor, fought tooth-and-nail to remove two 5-year-old African-American twins from their black grandmother’s care and give them to a single white adoptive mother on Milwaukee’s south side over the objections of the grandma, aunt, and a highly regarded black judge, Wisconsin Right Now has documented.

The Milwaukee grandmother, Margaret Hudson, initially lost the twin boys, Darryl and Durrell, because she did not have a big enough house, court records show. In fact, that was the “only obstacle,” Protasiewicz admitted in a court brief:

The grandmother, then in her 60s, fought ferociously, and ultimately unsuccessfully, to raise her own kin. “They are my grandchildren. They ain’t anybody else’s. They’re mine, and I want them with their brothers and their sisters, and I want them with me,” Margaret told the court, to no avail.

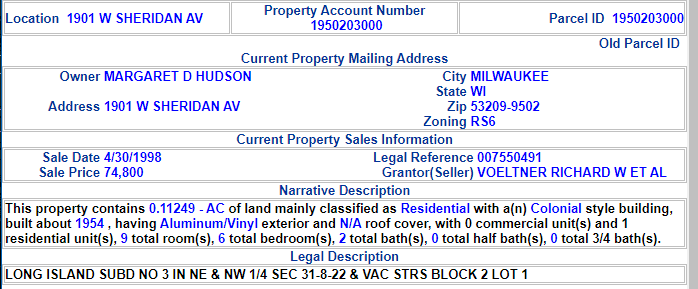

One of the most shocking angles in the 1999 case, however, is that property records show that Hudson, who skipped family reunions and social events to scrimp and save for years, DID manage to eventually buy a bigger house along Sheridan Avenue in 1998, but Protasiewicz continued trying to take her grandkids away anyway.

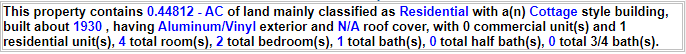

One of the twins, Darryl Guentner, told WRN that his adoptive mother’s house was smaller than the new six-bedroom house that Hudson purchased, although there were more people in the latter. But even that was not enough for Protasiewicz and others in the system.

A social worker opined that he did not believe Hudson, who worked in social services agencies, was as “committed” to the twins as the new foster mother because it took Hudson three years to get the house, court records say.

“We are a family, and we need to be together as a family,” Hudson told the court. “I’m sorry if it took me too long, and I don’t apologize for it. I did the best I could, and I’m going to keep on doing the best I can. Those are my grandchildren.”

But Protasiewicz wrote in 1999, when she was still trying to take the twins from the grandmother the year after she bought the home, that Margaret put her own “financial self-interests” ahead of the boys by not getting the bigger home sooner because she felt the “rent” was “excessive.”

“These actions clearly are not the actions of a grandmother, who in her own words believes ‘families take care of families,'” Protasiewicz wrote in the brief.

The foster mother was a relatively new presence in the boys’ lives.. Indeed, the white foster mother only had cared for the boys since March 1998, the same time Margaret initiated the process of purchasing the new 6-bedroom home, closing on the home in April of 1998. Yet even the next year, Protasiewicz was still arguing to the Supreme Court that Hudson should lose the boys.

The grandmother did not have a criminal history. There was no history by her of child abuse, neglect or substance abuse, court records show. She had a good job, working for social service agencies and women’s shelters, her daughter Denise Goggans says. The twins’ parents had essentially abandoned them, the mother to drug addiction, the family says.

If she had learned about the racial slur allegations then, Goggans says, “I would have to question, whether or not she looked at us as humans or she looked at us as the N word.”

Listen:

One thing that particularly grates Goggans is that the government gave the adoptive white mother thousands of dollars to care for the twins, after pressuring Hudson to get a bigger house, she says.

“They told her she (the grandmother) needed a bigger house,” says one of the twins, Darryl Guentner, now a 30-year-old security guard. “My grandma already had my brothers and sisters already. We were the last of the kin. That was the problem. To be honest with you, in retrospect my grandma should have won that.”

For years, Margaret had been taking in her grandkids, and she was caring for five already; indeed, many grandmothers like Hudson were holding their families together in a 1990s-era city shattered by the crack cocaine epidemic and crime explosion. In fact, Hudson has raised 11 kids.

However, Goggans said the system, including Protasiewicz, did not appreciate how much support Hudson had from herself and other family members. The children had “a village around them,” she said.

Protasiewicz spent 18 years as a prosecutor in Children’s Court, according to her judicial application to then-Gov. Scott Walker. For years, she handled countless petitions to terminate parents’ rights and place children in protective services. The cases she worked on are shrouded mostly in secrecy; it can be difficult to get access to children’s court records like these.

Margaret Hudson stands out because the diminutive, strong-willed grandmother fought the case all the way to the state Supreme Court on which Protasiewicz, now a liberal Milwaukee judge in Family Court, wishes to sit.

The case is known as “State v. Margaret H.” The twins are “Darrell and Durrell T.H.” The last names are given in court documents by only initials. Wisconsin Right Now’s journalists spent days tracing the family; the family did not seek out the media. We found the case because Protasiewicz mentions it in her judicial application to Walker as an accomplishment.

The family did not appear to be political at all; rather, they wanted to talk because they are still unhappy about how their family was treated.

We knocked on doors throughout Milwaukee’s north side. That eventually led us to one of the twins, Darryl Guentner, now a 30-year-old security guard with no criminal history, formerly Darryl Toliver-Hudson. Today the twins still carry their adoptive mother’s name. Darryl says he faces less racism when seeking jobs as a result. We asked him to see if the adoptive mother would talk to us as well, and he said he would try.

Although Protasiewicz also argued to the state Supreme Court that the grandmother’s bond with the twins was not substantial, even though the trial judge thought it was, the bond between Margaret and the twins today burns bright despite years of separation that Protasiewicz helped cause.

“My grandma, that’s my rock,” Darryl says today. “That’s my hardcore lady. She loves me. I’m her favorite. My grandma is my everything, The bond for us is very, very strong.”

Darryl disputes Protasiewicz’s court-brief argument that the grandmother had limited contact with her grandsons before they were taken away. Goggans says Protasiewicz did not bother to get to know the family and its dynamic. Goggans said that she was the one who would often pick the kids up from foster care, and she would take them to Hudson’s home on many occasions because Hudson did not drive.

“Up until the court was finalized, we always had passage with our grandma and our nana,” Darryl says, referring to Hudson and Goggans. “These two were in our lives together through thick and thin. I can remember personally going to my grandma’s house, seeing my grandma all the time. Sitting down and watching wrestling as a group with family members. Going to my nana’s house.“

Milwaukee radio talk show host and community advocate Tory Lowe tells Wisconsin Right Now it’s a story that has played out in the black community too many times for generations, leaving many wounds and touching painful nerves. He told WRN that, if Protasiewicz used racial slurs, he would expect to find some corollary harm or injury to black families involved in her cases.

Lowe has discussed the racial slur angle extensively on his radio show on 101.7 “The Truth,” which reaches a large black audience, even though most of the news media have censored the information.

“My concern is whether it affected families,” he told us.

Protasiewicz described it as a “very fulfilling experience” and “rewarding”

When she unsuccessfully asked then-Gov. Scott Walker to appoint her to a judgeship, Protasiewicz touted the case. She wrote that she had the “honor” of arguing the case before the state Supreme Court in 2000 and said the state “prevailed.” She described working on the case as a “very fulfilling experience” and “rewarding.”

Hudson was “originally slated to be the twins’ primary caregiver and was made the twins’ guardian in February of 1995,” the appeals court records say. “Her apartment was too small to accommodate the twins and the five children who were living with her,” so efforts were made to place the twins in foster care.

Hudson was “originally slated to be the twins’ primary caregiver and was made the twins’ guardian in February of 1995,” the appeals court records say. “Her apartment was too small to accommodate the twins and the five children who were living with her,” so efforts were made to place the twins in foster care.

Protasiewicz’s main argument was that the boys would have more stability with the more empathetic, in her view, white foster mother. She wrote that psychologists and social workers supported leaving the boys with the foster mother because they were doing better in her care after having cycled through a series of foster homes after the grandma didn’t get the bigger home.

However, Protasiewicz argued to the Supreme Court in 1999 that the woman’s relationship with the children was stronger.

Protasiewicz asked the court to “free” the children for adoption, court records show.

We asked Protasiewicz if she regrets the case today; the boys eventually ended up adopted by the white woman, but it only injected more chaos into their lives as Darryl describes, the adoptive mother suffered through health and financial problems, and relationships that came and went, including with someone who ended up incarcerated. At times, the boys would run away.

Protasiewicz did not respond.

Eventually, the twins ended up with the adoptive mother’s relatives and then, finally, at age 13, were placed back with their aunt, Denise Goggans.

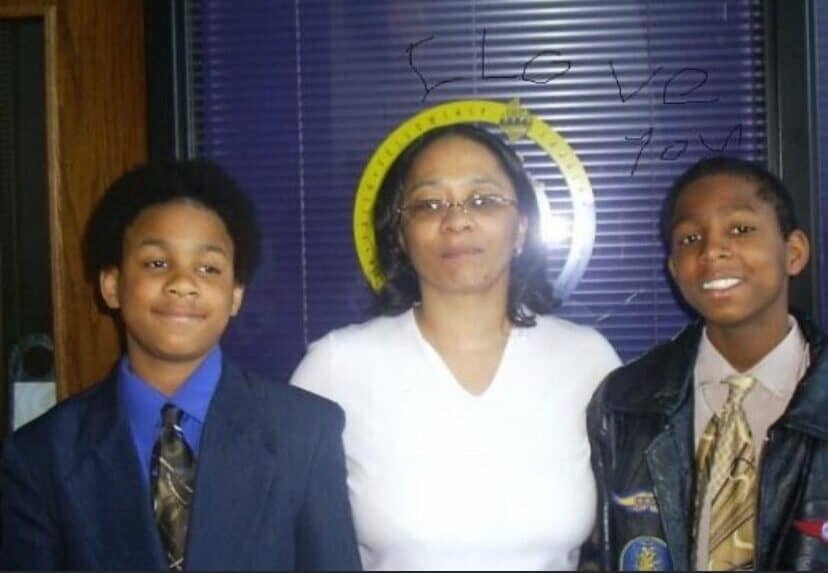

Here is a picture the boys sent Goggans, who is Hudson’s daughter, around that time. One of them had scribbled “I love you” in a child’s handwriting to the aunt.

‘A Bone in the Side About Our Family’

Denise Goggans, Margaret’s daughter and the twins’ aunt, told WRN that the elderly Hudson, a St. Louis native who has a stern and very forthright personality, was also penalized because she would not get down on the floor to play with the twins. “I think she (Protasiewicz) had a bone in the side about our family,” Goggans said, who believes Protasiewicz acted coldly to the family and didn’t take the time to really get to know them.

If Protasiewicz used racial slurs around that time, it’s “deplorable,” she added. Goggans wonders if her mother’s stern attitude and “sharp tone,” turned off Protasiewicz, or her age, or “what her position was and what she could do with it against a family that was African-American.”

“They screwed her,” Darryl says plainly of Hudson. “You had two strong independent black women trying to fight,” he says of Hudson and Goggans. “Every need, we would have needed, we had it. Transportation, food, and clothes, we would have had it. We should have never been placed out of our family.”

In her brief to the court, Hudson’s attorney Jennifer Abbott accused Protasiewicz of “disingenuously” presenting a dispute over the number of times the twins’ blood family had visited them in the “light least favorable” to Hudson. Although Protasiewicz argued that Margaret only had 12 visits with the twins in their first four years of foster care, those were only the Children’s Service Society records of visits, Abbott wrote. Hudson didn’t drive, so Goggans would pick up the kids and bring them to Hudson’s home every other weekend, meaning the grandmother was seeing the kids a lot more than those records indicated. Goggans confirms this.

Appeals court records say that Margaret, who was also raising the twins’ siblings, was criticized by a psychologist for not being as “affectionate or playful” with the boys as the white woman, although she was described as “firm and attentive to them,” directing them to recite the alphabet and playing a game of tic-tac-toe.

In her brief, Protasiewicz focused on the drug problems of three of Margaret’s eight children, as well as the criminal histories of three of them (Goggans and Hudson have no criminal history.) In contrast, she described the white adoptive mother as showing “empathy and sensitivity.”

‘Never wavered in her desire’

Milwaukee County Circuit Judge Joe Donald believed Hudson should get the boys.

According to his April 6, 1999, order, “A re-integration of the children into their biological family is in their best interests because the children have a substantial relationship with their grandmother, Margaret H., and it would be harmful to sever that relationship.” He ordered plans to be developed to transition the children “into the home of the maternal grandmother.”

Despite that language, Protasiewicz told the Supreme Court that Donald had erroneously “failed to consider the best interest of the children.” Of course, families in these situations often face a catch-22 situation; the longer they fight and a case drags on, the longer the children develop bonds with the adoptive family, making it easier for the system to argue it’s in the children’s “best interests” to stay with the adoptive family and harder for the blood family to argue otherwise.

Donald said in court that the grandmother “never wavered in her desire or her love for her grandchildren. She has had many difficulties to overcome. When I first came on the bench, it never occurred to me that there are people out there who can essentially walk away from their children – and I’ve see a lot of that — but this is not that kind of a case.”

The grandmother, Donald said, “has been trying. She has made every attempt to put herself in a position and at this time I just can’t take that away from her.”

But Protasiewicz had no problem doing so. In fact, she has touted her efforts to remove the twins from Margaret’s care on her resume.

Protasiewicz appealed Donald’s decision to the state Supreme Court. The appellate court reversed Donald, characterizing the case as a “custody dispute” between the grandmother and the 42-year-old white childless foster mother who wanted to adopt them. The court found that Donald placed the feelings and efforts of the grandma over the best interests of the kids, should have considered more factors, and remanded the case back for additional proceedings.

Hudson went to the Supreme Court, which declined to terminate the grandma’s rights, but also sent the case back to the Milwaukee court, which eventually gave the boys to the adoptive mother as a result of the new decisions, Goggans says.

The adoptive mother worked as an engineer making neon lights and then in accounting.

‘We stick together

Today Margaret Hudson is 87 years old. Her health is slowly failing. She still lives in the Sheridan home she bought to get the twins. Her memory is fading, and her memory of Protasiewicz is minimal now. Her determination to keep her family together at all costs burns just as ferociously as it did back in 1999.

On keeping family together, Margaret tells us, “That’s what you’re supposed to do. It’s always been important to me. I was raised in a family, and we stick together. That’s what families do. They stick together, they help each other, they take care of each other. That’s why it’s important to me.”

In a 2006 decision, the Wisconsin Supreme Court wrote, “The United States Supreme Court has recognized a parent’s fundamental right to the care and custody of his or her child and concluded that a state may not terminate this right without an individualized determination that the parent is unfit.”

Margaret Hudson’s Home Description From Tax Records

Adoptive Mother’s Home Description From Tax Records

(Name and address intention removed to protect the adoptive mother’s identity)

Racial Slur Allegations

The case wound through the court system from 1995 to 1999 and spans, in part, the time frame when Protasiewicz is accused of using the “N-word” to refer to blacks, according to two men who say they heard her use the racial slur directly in 1997, her former stepson, Michael Madden, and a former restaurant/bar owner named Jon Ehr, whose attorney dad knew Janet’s then-husband. She has denied the accusations to other media outlets, although she never responded to a request for comment to us.

Michael Madden told us that he heard Protasiewicz use the “N-word” to refer to black parents in Children’s Court and other cases, while ranting about the drug wars.

Darryl told us it “hurts” to hear that Protasiewicz might have used racial slurs. “People’s kids need to be with their families,” he adds.

“We were two black kids with one single white mother,” Darryl says. “The society we stayed in was dominant white. We were the first two black kids in our church. We had our differences. It wasn’t bad but wasn’t good.”

Darryl says he “felt like an outcast” when he visited his blood family, and he says the visits became less and less frequent after the adoption until Goggans got the boys back at age 13.

“It was very hard for me to go back to the north side back to my birth side of the family. They know who I was. They know I was a twin. But I didn’t know them for them,” he says.

Goggans said she swept in and got custody back after discovering the adoptive mother had left the boys with her relatives for “months.”

“They left as a package; they come back as a package,” she said.

Today Darryl must cautiously straddle two different families across two very different worlds. His twin, Durrell Guentner, who did not want to comment for this story, is planning to change his name back to his birth family’s surname, Darryl says. Darryl says he tries to stay neutral; today, he finds value in both families and says both experiences brought him some positive things. He believes the adoptive mother tried to care for them and doesn’t want to say anything negative about her. But he says Durrell, whose life has gone on another trajectory through serious troubles with the law, aligns more firmly with their blood relatives.

We have the name of the adoptive mother, but we aren’t naming her at the request of Darryl, who doesn’t believe she is the villain of this story.

“The villain would be in the courthouse, Janet,” he says.

According to Donald’s order in the case, which Protasiewicz appealed to higher courts, Darryl and Durrell were first found to be in need of protection or services on May 3, 1993. This was due to their mother’s drug use, according to Goggans. Today, Darryl says his mother is recovered from addiction and he has a loving and close relationship with her too.

The appeals court records says the boys were in multiple foster homes before the foster mother sought to adopt them. Psychologists and social workers said the twins should continue to live with the foster mother and that she should be able to adopt them, according to the appeals court case, because they had bonded with her, started calling her “Momma,” and “she was more capable of addressing their special needs than was the grandmother” because they suffered from reactive-attachment and attention-deficit disorders, the court records say. They believed the grandmother “may not have an accurate assessment of the extent of these boys’ special needs and ability to respond to them effectively.”

The decision says that psychologists thought the foster mother would give the boys stability but that they should be allowed to see their birth relatives. Case law at the time said the court had to determine the best interests of the child and must consider factors such as the likelihood the child would be adopted; the ages and health of the child and amount of time outside the home; the wishes of the child; whether the child has substantial relationships with the parent or other family members and whether it would be harmful to the child to sever these relationships, and whether the child would be able to enter into a more stable and permanent family relationship.

Donald’s order says the children were initially placed in foster care. Darryl says they were in several different foster homes.

Abbott wrote, though, that the state’s own witness testified that the grandma had a substantial relationship with the boys. Even Protasiewicz admitted that the grandmother was seeing the twins on a “regular basis” by 1998, the year she bought the house, and Protasiewicz appealed to the state Supreme Court – a court on which she wishes now to sit.