A former Milwaukee Public Museum exhibit designer, Emilio Bras, is sounding the alarm about what could happen to the museum’s artwork and historic exhibits if the museum moves to a new $240 million building.

With good reason.

In a recent interview about the new museum project, the museum’s earned media director, Madeline Anderson, admitted, referring to the iconic Streets of Old Milwaukee and European Village exhibits: “These exhibits, these buildings and other murals, those are painted on or built into this structure. Even if we wanted to, we couldn’t just bring them over to the new building.”

“Which murals, specifically?” we asked. The museum officials won’t say. Meanwhile, the history and arts communities remain silent. Historian John Gurda even wrote a recent column favorable to the project while ruminating about tossing out history (and art), saying, “What to keep and what to toss? How much of our earlier lives is worth preserving, and how much is just dead weight?”

In an interview with Wisconsin Right Now, Bras confirmed that it won’t be possible to fully move the Streets of Old Milwaukee and European Village. “You would have to destroy it, take a hammer to it,” he said.

As a designer who worked on Milwaukee Public Museum exhibits for decades before retiring last year, this troubles him deeply. The current Milwaukee Public Museum “is the perfect example of the creativity of individuals,” Bras said.

The Streets of Old Milwaukee is a historic exhibit; it was designed by an artist named Edward Green in 1965. According to the museum, it was “one of the first walk-through dioramas in the world.” We previously interviewed the granddaughters of the Serbian immigrant who helped painstakingly curate the adjacent European Village. There are petitions to save both.

Bras is also deeply concerned about the fate of the many murals referenced by Anderson.

Anyone who has been to the Milwaukee Public Museum has felt the pull of the murals; the intricate paintings pull you into the scenery.

According to Bras, the murals, which are prominently displayed throughout the current museum, are “important because they show a period of art that was just part of the history of the nation. An art museum is not going to see them as works of art, but they are a work of art. The artists who created those pieces are no longer around, so if you destroy them, you won’t be able to get something like it. It’s not going to be the same. You want to protect them.”

After interviewing Bras, Wisconsin Right Now asked Anderson and the museum’s public relations firm, Mueller Communications, for a list of the artwork in the current museum that can’t be moved to the new one. We also asked for the names of the painters and what will happen to the art. Specifically, will it be destroyed?

We asked:

“Can you please provide us with a list of the artworks and murals in the current museum and by which artists and which ones the museum will be able to move and which will be destroyed or just left behind in the old/current building? For example, there are many beautiful paintings that form the backdrops of exhibits and dioramas. I am trying to trace the works of art and artists in the current building. Madeline told Fox 6 that many can’t be brought over, and we would like a list.”

We Have Not Received a Response.

With the museum officials silent on the art, we turned to historical archives and biographies to trace the artists who have worked in the Milwaukee Public Museum over the years.

One artist who left his legacy on the museum was Robert Frankowiak. “In 35 years with the museum, Bob painted over 47 murals and diorama backgrounds depicting wildlife ecology of Africa, Central America and North America, traveling extensively to collect specimens and painting afield. He rose from staff artist to become the museum’s art director in 1984,” his 2017 obituary reads. He retired in 1990.

He worked under renowned wildlife artist Owen Gromme for a time.

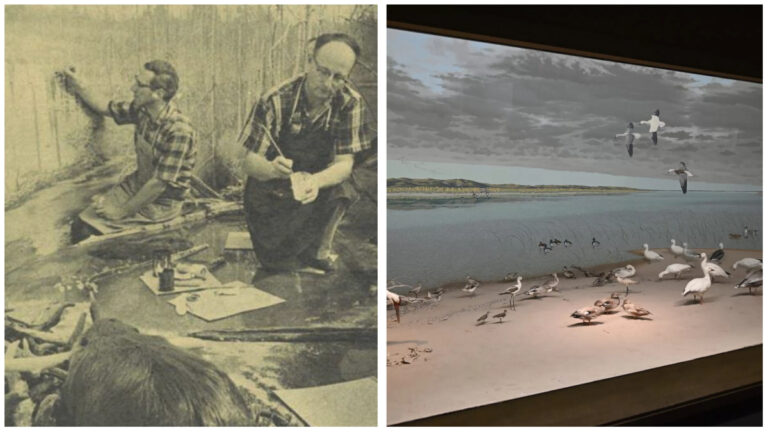

Another artist who was involved in the museum is Sylvester J. Sowinski. A biography for Sowinski demonstrates the deep historical roots in the museum’s artwork. See a photo of Sowinski working on museum artwork here.

He is described by Wisconsin History.org as a “Milwaukee artist.”

That website says that “after service in World War Two, Sowinski trained at the Wisconsin Academy of Art and the Layton School of Art before working as an independent commercial artist and illustrator, from 1948 to 1963.”

“In the latter year, he was appointed chief sculptor of the Milwaukee Public Museum, where he created 47 human figures which populate the Masai lion hunt, Eskimo igloo group, European Village, and other exhibits,” the bio says.

“He also painted backgrounds in dioramas and murals. His work, which shows the influence of Frederic Remington and N.C. Wyeth, among others, can also be found in private and public collections, the Natural History Museum in Racine, Wis., and the Manitowoc Maritime Museum.”

Although museum officials told Milwaukee County that they would have new exhibit story lines by 2020, they tell Wisconsin Right Now that they don’t know yet which exhibits will be in the new facility. Construction is planned for December 2023, even though the project is $107 million short in private donations.

Bras worked for 34 years in the Milwaukee Public Museum’s exhibit department as a designer, with skills in object installation, mount-making and lighting design. According to his LinkedIn page, before retiring in 2022, he “participated in over 80 different theme exhibit installations.”

“You will have to do it new; you would have to rebuild it,” he said of the Streets of Old Milwaukee exhibit. “You can’t move it as you have it now here. It was built by carpenters; there’s wood, nails and glue. You can’t lift it up and carry it with you. You would have to destroy it; take a hammer to it. You would have to do an interpretation of it.”

As for the historic dioramas? “You can remove the foreground; you can take out the animals; there are pegs in their feet. Just lift them straight up. The plant material and rocks are all fake. You can remove and bring that with you. You can recreate a diorama,” Bras said.

But that’s not true of other exhibits and murals.

“Our museum brought the world to Milwaukee. We brought Africa, we brought China, we brought Japan to them – different parts of the world to them. All of a sudden, you’re going to take this away,” Bras said.

He said that other exhibits can’t be moved without “destroying or moving a part of it. Those shells are bigger than a freight elevator; they would have to cut a hole in the side of the building to cut those shells out. They are several layers of cement.”

He said some museums have been able to move exhibits by cutting them and taking “them out in pieces. They hire an expert to fix the scene and match the paint.”

A New Style of Exhibit Is Born in Milwaukee

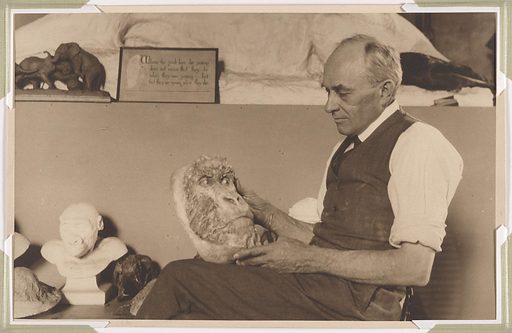

According to Bras, a taxidermist named Carl Akeley “created the whole idea” of the dioramas in the current museum. Previously, animals “were just in glass cases with very little explanation and names,” he said. Akely created the idea of putting animals in their natural environments “to show how they live,” he said.

The Field Museum website confirms that Akely is “widely considered the Father of Modern Taxidermy.” Born on a farm in New York, he worked for various museums throughout his career.

In 1886, Akeley started working for the Milwaukee Public Museum, “first as a contractor, then as staff taxidermist,” Field Museum reports. “During this period, Akeley was an early adopter of a manikin method comprising a wooden armature bulked out with wire mesh to form the animal’s contours.”

The article notes: “In 1890, he produced a habitat diorama of muskrat life, which remains a landmark in the history of dioramas. He left the MPM in 1892 to pursue contract work, and made another taxidermic splash with three broncos for the Smithsonian’s exhibit at the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893.”

According to Britannica, Akely “developed the taxidermic method for mounting museum displays to show animals in their natural surroundings.”

Bras says that the “start of the dioramas” occurred in Milwaukee. The concept soon spread to other museums.

Just as influential: the paintings historically attached to the museum.

According to Bras, “many of the German painters started coming and working at the museum.”

The Rich History of Art at the Milwaukee Public Museum

Many of the well-known artists who painted for the museum did so well before the 1960s when the current museum was built. Thus, it’s not clear which of their paintings would be destroyed, if any, and which murals Anderson was talking about exactly.

Bras believes some of the paintings might be easily moved; however, the fact remains that the museum is not providing a full accounting to the public, and the rest of the media aren’t asking.

The museum was officially chartered in 1882, but its “existence can be traced back to 1851 to the founding of the German-English Academy in Milwaukee,” the museum’s website says. The current building was completed in 1962.

According to a column by historian John Gurda in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, “MPM moved to 800 W. Wells, one collection at a time, between 1962 and 1967.”

There is no question that the Milwaukee Public Museum has a storied legacy of historic art, much of it deriving from the era when Milwaukee was the hub of German and Austrian panoramic painting styles.

“A lot of these were Germans and came to Milwaukee. They were artists,” said Bras, who added that paintings in the federal courthouse in Milwaukee were made by some of the same artists.

The museum does provide some glimpses into the dioramas and artwork on its website.

Some of the murals date to Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration, according to the museum’s website.

“One of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal administration policies, the Works Progress Administration, offered jobs to keep people employed during the Great Depression,” the museum’s website says.

“At the Milwaukee Public Museum, Director Samuel A. Barrett wanted to keep his staff employed, so he designated space for murals throughout the Museum to depict different exhibits and periods in world history.”

According to the museum, the Plains Indian Hunt “was the creation of taxidermist Walter C. Pelzer, a member of the Museum staff from 1932-1972. The inspiration for this exhibit came when a large bull bison was obtained by the museum. This exhibit opened in 1966 and would become the largest one known in the world at this time.”

According to the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee, a Viennese panorama painter, George Peter, created state-of-the-art dioramas for the Milwaukee Public Museum. The encyclopedia reports that “between 1885 and 1890, Milwaukee was a center for panoramic painting in America.”

Another biography says Peter “was a panorama painter with a specialty in painting animals. He pursued a long career with the Milwaukee Public Museum creating numerous backdrops for large dioramas.”

Milwaukee History.net also reports on “George Peter, who created the dioramas in Milwaukee’s Public Museum.”

The museum’s first Curator of Anthropology, Samuel A. Barrett, was also responsible for life-sized dioramas, according to the museum’s website.

“Along with MPM artist George Peter, Barrett consulted with local people to create life-sized dioramas, hoping to achieve the highest degree of accuracy in his depiction of Kwakiutl life before the widespread arrival of European settlers,” the website says.

“Though some of these dioramas have undergone renovation since they were installed, the MPM still houses most of these early life group displays.”

The museum’s website labels the painting below Barrett’s “Northwest Coast Diorama at the Milwaukee Public Museum.”

Myron Nutting, a Paris-educated painter, painted murals for the Milwaukee Public Museum in the early 1930s. In 1936, Nutting “painted murals of the Athenian Acropolis and an ancient Egyptian mummification scene for the Milwaukee Public Museum.”

According to Urban Milwaukee, panorama paintings “would prove to be a short-lived trend, nearly disappearing by the 1890s (though the style had an impact on the dioramas devised by artisans at the Milwaukee Public Museum, which in turn influenced other natural history museums).”

Bras says of the collections, “All of these objects are precious and very valuable. Moving the collection – it’s not like you can just throw stuff in boxes and carry it across the street.”

He said that the museum has continually worked to update and evolve its exhibits. He said that the Streets of Old Milwaukee is constructed in part from doors that were salvaged from old houses that were being torn down in the city, and the real doors from the front entrance of the Pfister Hotel are in the museum.

“They wanted to represent Milwaukee at the turn of the century; when you walk through the streets it goes from gas to electricity,” Bras said.